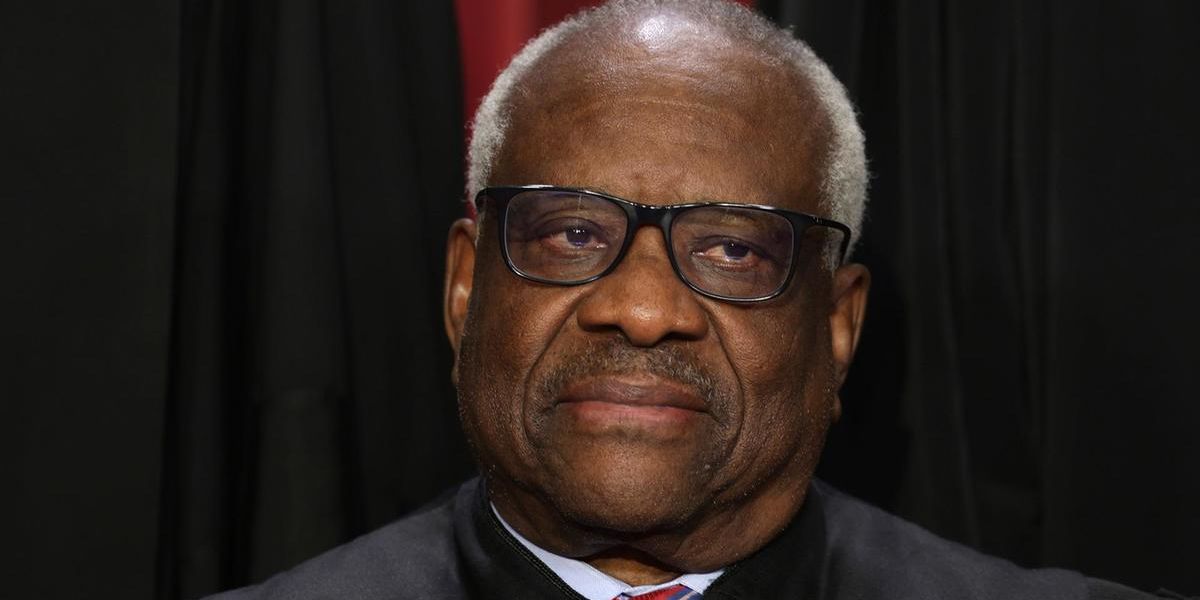

Justice Clarence Thomas stood alone in an 8-1 decision Friday that upheld a federal statute prohibiting domestic abusers from obtaining firearms. The decision is the Court’s first on handguns since New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, which overturned the state’s handgun licensing regime in 2022.

Zackey Rahimi and the Underlying Conflict

Zackey Rahimi’s ex-girlfriend accused him of beating her. He subsequently agreed to a restraining order that prevented him from harassing, stalking, or threatening his ex-girlfriend and their child, as well as from carrying a firearm.

Despite having consented to the limits, Rahimi went on a two-week binge of violence, including five different shootings in Texas. When law authorities caught up with Rahimi, they discovered a rifle and a pistol at his residence. Rahimi was convicted of illegal gun possession under 18 U.S. Code § 922, which he later challenged as an unconstitutional violation of his Second Amendment rights.

18 U.S. Code Section 922 (g)(8) prohibits anyone from possessing firearms if they are “subject to a court order that restrains [them] from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner.”

A three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, comprised of U.S. Circuit Judges Edith Jones, a Ronald Reagan nominee, and James Ho and Cory Wilson, both Donald Trump appointees, unanimously sided with Rahimi and overturned his conviction.

The Biden administration appealed, and the Supreme Court overturned the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

The Supreme Court applies Bruen

In Bruen, Thomas stated that the “unqualified command” of the Second Amendment is for enforceable gun rules to be “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” Bruen’s decision was based on the 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision, in which Justice Antonin Scalia stated that Second Amendment guarantees only apply to “ordinary” or “responsible” law-abiding citizens, a category that the Biden administration argued Rahimi and other domestic abusers do not fall into.

The Rahimi opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts for a virtually unanimous vote, stated that the Court had “no trouble” concluding that the law in dispute was constitutional. Roberts cited the Court’s ruling that the right to keep and bear weapons is a fundamental right under the Second Amendment. He acknowledged that, “some courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases,” and he added, “These precedents were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber.”

Roberts noted from the Bruen decision that, while a gun regulation “must comport with the principles underlying the Second Amendment,” it does not have to be a “dead ringer” or “historical twin.” According to Roberts, Section 922 (g)(8) is consistent with historical precedent.

“From the earliest days of the common law, firearm regulations have included provisions barring people from misusing weapons to harm or menace others,” the top justice said, before diving into numerous incidents from English history in which people were disarmed. Roberts observed that as early as the 1600s, dangerous individuals, political opponents, and even “disfavored religious groups” were routinely disarmed.

Roberts clarified that the current finding does not imply that persons suspected of posing a unique danger should be barred from carrying firearms, but rather distinguishes such a group from those who have been judged credibly dangerous.

A flutter of concurrence

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a concurrence, which was joined by Justice Elena Kagan, in which she raised an ongoing objection to the “wrongly decided” Bruen decision. Sotomayor stated that, even under the Bruen test, the conclusion was “an easy case.”

Sotomayor also criticized Thomas for applying Bruen too rigorously.

“If the dissent’s interpretation of Bruen were the law, then Bruen really would be the ‘one-way ratchet’ that I and the other dissenters in that case feared,” Sotomayor wrote in her concurrence.

She went on to argue that, according to Thomas’ logic, a legal solution to a problem must fit history, even if the underlying problem has altered significantly.

“Given the fact that the law at the founding was more likely to protect husbands who abused their spouses than offer some measure of accountability, it is no surprise that that generation did not have an equivalent to §922(g)(8),” Sotomayor wrote in reference to “Bruen’s myopic focus on history and tradition.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a solitary concurrence in which he stated that the concept of requiring a historical counterpart is not entirely negative.

“Courts must proceed with caution when making comparisons to historic firearms regulations, or else they risk gaming away an individual right that the people expressly reserved for themselves in the Constitution’s text,” Gorsuch warned, before stating that the Court got it right in Rahimi’s case.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh also wrote a lone concurrence, emphasizing the necessity of sticking to the wording of the Constitution and stating that even an originalist interpretation of American law has long acknowledged that “constitutional rights generally come with exceptions.”

Kavanaugh compared judges to umpires, stating that their role is to adhere strictly to the text and not interject policy or personal ideas. Kavanaugh then gave a detailed overview of the Court’s long-standing practice of using history to resolve decisions concerning individual rights. Balancing multiple interests during the decision-making process “can be antithetical” to the idea of judges serving as umpires, according to Kavanaugh.

“It turns judges into players,” the justice explained.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett also authored her own concurrence, which began with the remark that “the Second Amendment is not absolute,” before going into the essential concepts of originalism.

Barrett remarked that “reasonable minds sometimes disagree about how broad or narrow the controlling principle should be,” but that the Rahimi decision was correct.

In her single concurrence, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson stated that if she had been on the Court when Bruen was decided, she would have dissented; but, given its current status as binding law, she concurs with the Rahimi decision.

Jackson stated that the rules outlined in Bruen are simply ineffective because they promote confusion.

“The message that lower courts are sending now in Second Amendment cases could not be clearer,” says Jackson. “They say there is little method to Bruen’s madness.”

Jackson contended that Bruen’s history-and-tradition approach not only burdens courts, but also produces inconsistent conclusions that are even more troublesome than gun rulings before Bruen was decided. Jackson finished by stating that courts are “currently at sea” and require “a solid anchor” when considering weapons issues, adding that both courts and the public want clarification.

Thomas stands alone

Only Thomas dissented, claiming that Section 922(g)(8) violates the Second Amendment. Thomas stated that the government completely failed to demonstrate any historical analogy to the statute, and that this failure is “unsurprising,” because Founding-era laws would not have responded to domestic abuse by disarming citizens. Thomas explained that surety laws were utilized at the time to suppress interpersonal violence.

Thomas blasted the Biden administration’s position in the case, calling it “a blatant attempt to refashion this Court’s doctrine.”

Thomas compared the government’s attempt to deprive “dangerous” people of firearms to the treatment of Black Americans during slavery and its aftermath.

“The Government peddles a modern version of the governmental authority that led to those historical evils,” Mr. Thomas added.

“Its theory would allow federal majoritarian interests to determine who can and cannot exercise their constitutional rights,” according to him.

According to Thomas, “in the interest of ensuring the Government can regulate one subset of society, today’s decision puts at risk the Second Amendment rights of many more.”

Thomas finished by stating that there is already a mechanism in place to deprive dangerous criminals of their guns: states may simply prosecute and imprison them.